Introduction

“Rwanda is like a phoenix rising from the ashes.”

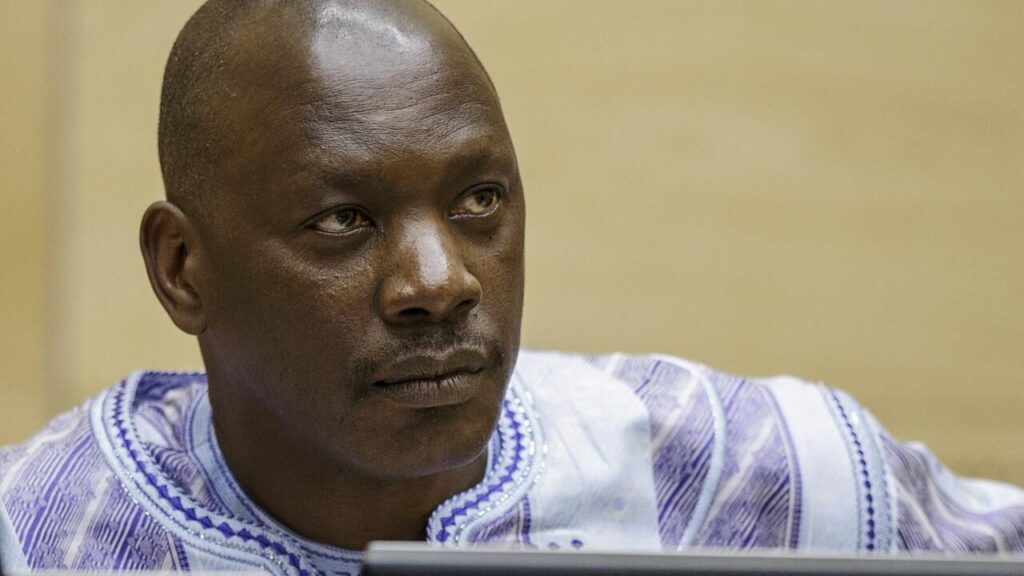

This is how many observers describe the country’s dramatic transformation after the devastating 1994 genocide that left over 800,000 people dead. Today, Rwanda stands as one of Africa’s most stable and economically successful nations, with many pointing to its governance model under President Paul Kagame as a key factor in this success. But can Rwanda’s approach truly serve as a model for Africa? Or does its balance between stability and authoritarianism raise concerns about democracy and human rights?

This article explores Rwanda’s approach to governance under President Paul Kagame, evaluating its achievements, challenges, and potential as a model for African nations. it delves into how Kagame’s leadership has fostered a sense of national unity and economic revival since the 1994 genocide, often cited as a success story in Africa and highlights Rwanda’s strategic efforts to build robust institutions that prioritize transparency, accountability, and citizen participation.

However, the article also addresses critiques in exploring concerns about political freedoms and human rights limitations that accompany Kagame’s centralized rule by analyzing his approach of prioritizing stability and development, even when it comes at the cost of democratic freedoms.

The Kagame Era: Stability and Progress

Since coming to power in 2000, Paul Kagame has overseen Rwanda’s reconstruction and development. Under his leadership, the country has achieved remarkable feats: poverty reduction, increased literacy rates, widespread healthcare coverage, and a booming tech sector. Kigali, the capital city, is often cited as one of the cleanest and safest cities in Africa.

According to the world Bank Group(2024), from 2009 to 2019, rwanda’s GDP grew at an average of 7.2 %, However, after growth of 10 % in 2019, the restrictive measures and protocols instituted to control the Covid 19 pandemic curtailed economic activities, with the GDP shrinking by 3,4% in 2020, the largest drop since 1994.

In 2019, the mean years of adult education in Rwanda was estimated to be 4.7 years, almost equal to the average of 4.6 years for low-income countries on the continent, and the average test score for primary students in Rwanda stood at 24.7 slightly below the average of 27.2 for its income peers in Africa. (World Bank Group,2024)

The Rwanda Governance Board: Institutionalizing Good Governance

A significant feature of Rwanda’s governance model is its structured and institutionalized approach to good governance. The Rwanda Governance Board (RGB) was established to ensure transparency, accountability, and efficiency in public services. It monitors government performance, sets clear targets, and emphasizes anti-corruption efforts.

The “Imihigo” system is another example of Rwanda’s approach to accountability. Under this system, government officials at all levels sign performance contracts with specific goals they must achieve within a set time (Daniel,2010). This results-based governance model has created a sense of responsibility and urgency in public administration, with measurable outcomes in education, health, and infrastructure. While statistics on service delivery before and after the introduction of imihigo were not available in 2010, anecdotal accounts suggested improvement.

In addition to imihigo, Rwanda drew on a number of other traditional practices to bolster its decentralization efforts at the local level. These included gacaca, a traditional form of dispute resolution in the justice system; umugunda, or monthly community work projects such as planting trees and repairing bridges and roads; and ubudehe, or participatory planning and budgeting at the village level. (Daniel,2010)

Authoritarianism: The Dark Side of Stability?

While Rwanda’s achievements are impressive, they come at a cost. Kagame’s leadership has been described as authoritarian, with limited tolerance for dissent. Political opposition is severely restricted, with critics often accusing the government of stifling free speech, imprisoning dissidents, and manipulating elections. Kagame has been re-elected multiple times, often with overwhelming majorities exceeding 90% of the vote, leading to accusations of electoral manipulation.

The balance between stability and authoritarianism is a central question in evaluating Rwanda’s governance model. While Kagame has delivered stability, economic growth, and improved living standards, his critics argue that this has been achieved by sacrificing political freedoms and human rights. The government’s tight control over the media and civil society, as well as its surveillance of opposition figures, has raised concerns about the long-term sustainability of Rwanda’s model.

Kagame’s Pragmatism: Stability First

Kagame has defended his approach on several occasions, arguing that Rwanda’s unique history necessitates a different kind of governance. The trauma of the 1994 genocide, during which ethnic tensions between Hutus and Tutsis exploded into violence, still casts a long shadow over the country. Kagame’s primary focus has been maintaining peace and unity, ensuring that ethnic divisions never again result in mass violence.

Rwanda’s government has adopted a “developmental authoritarianism” model, similar to the ones used by countries like Singapore and South Korea during their rapid development phases. The emphasis is on economic growth, stability, and social order, even if it comes at the expense of liberal democracy. For many Rwandans, the benefits of this approach; peace, security, and rising prosperity, outweigh the drawbacks.

Can Rwanda’s Model Be Replicated in Africa?

Rwanda’s governance model presents an intriguing question for other African nations: Can its combination of authoritarianism and stability be a viable model for the continent? In many parts of Africa, countries struggle with corruption, weak institutions, and recurring political crises. Rwanda’s centralized and disciplined approach could offer lessons for nations seeking stability and development.

However, replicating Rwanda’s model might not be feasible in all African countries. Rwanda’s small size and its post-genocide context make it a unique case. Larger and more ethnically diverse nations, like Nigeria or Ethiopia, may not be able to impose the same level of centralized control without sparking backlash. Additionally, Africa’s democratic trajectory is becoming more deeply ingrained, with growing demands for transparency, pluralism, and human rights.

Balancing Governance and Rights

The challenge for Rwanda, and other African countries inspired by its example will be finding a balance between maintaining stability and allowing greater political freedoms. As Rwanda continues to develop, the calls for more democratic reforms may grow louder. For now, Kagame’s model of good governance focused on stability, efficiency, and development, has proven effective in delivering tangible benefits to the people. But whether this model is sustainable in the long term, without greater political openness, remains to be seen.

Conclusion

Rwanda’s governance model under Paul Kagame presents both inspiration and caution for Africa. It demonstrates that good governance, efficiency, and accountability can lead to rapid development and stability, even in a country that has experienced one of the worst genocides in modern history. However, the authoritarian nature of Kagame’s regime raises questions about the future of democracy and political freedom in Rwanda.

While Rwanda’s successes should be acknowledged, African nations seeking to emulate its model must also be cautious of the risks posed by limiting political freedoms. Ultimately, the lesson from Rwanda may be that good governance is not just about stability, but also about the ability to evolve, adapt, and expand freedoms as societies grow.

Works cited

Daniel S. (2010) The promise of imihigo: decentralized service delivery in Rwanda, Innovations for successful societies. Princeton University. http://www.princeton.edu/sucessfulsocieties

Grajeda, M. (2021). Kagame’s ruse in Rwanda: The debilitating role of authoritarianism in Rwanda and its impact on long term, sustainable development [Master’s thesis, Chapman University]. Chapman University Digital Commons. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000322

Sundaram, A. (2014) Rwanda. The Darling Tyrant. Political magazine htpps://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/02/rwanda-paul-kagame-americas-darling-tyrant-103963/