Introduction

Is peace achievable through military might alone, or does sustainable stability require negotiation?

A key concern in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is President Felix Tshisekedi’s hardline stance against negotiating with the AFC/M23 rebel coalition group, which continues to entrench itself in eastern DRC’s resource-rich areas. Tshisekedi’s administration, focusing on a military response with the support of the “WAZALENDO” militia, risks prolonging the conflict. This approach raises questions about the sustainability of a no-negotiation policy in a region where armed confrontations have historically evolved into prolonged crises.

This article aims to analyze whether the refusal to negotiate with the AFC/M23 rebel coalition group is a sustainable strategy or if it inadvertently prolongs the conflict and instability in eastern DR Congo, given the region’s complex geopolitical landscape.

Context and Background

The M23 (March 23 Movement), formed in 2012 by former members of the CNDP, a rebel group once backed by Rwanda, continues to challenge the DRC government’s authority in the Kivu region. Despite multiple ceasefire attempts, the government designates M23 as a terrorist organization, refusing dialogue to uphold territorial integrity (Reliefweb 2023).

Meanwhile, the “Alliance Fleuve Congo” was officially launched in December 2023 in Nairobi by Corneille Nangaa, the former chair of the DRC’s Electoral Commission. This coalition, comprising 17 political parties, two political groupings, and several armed groups including the M23, aims to restore DRC’s sovereignty and end instability caused by state weaknesses (africanews 2023).

Despite military responses from the DRC Armed Forces (FARDC) and allies from the EAC, SADC, the Wazalendo militia, and mercenaries, AFC/M23 remains resilient. According to MONUSCO, the group has gained sophisticated weaponry, allowing it to expand control over strategic areas. This raises questions about the efficacy of Tshisekedi’s no-negotiation stance—will it bring peace, or perpetuate conflict and humanitarian crises?

The Cost of Refusing Direct Dialogue

History in the Great Lakes region shows that military-only approaches without dialogue often worsen conflicts rather than resolve them. The DRC’s refusal to negotiate with AFC/M23 mirrors past hardline strategies that led to recurring violence. AFC/M23’s resilience challenges Tshisekedi’s administration, as the group’s presence disrupts communities, displaces civilians, and strains resources in the Kivu provinces.

Regional conflicts offer instructive lessons. For example, Sudan’s civil wars showed that insurgencies rarely end with military force alone; only with the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement did a peace process begin, though fragile (Ottaway & Hamzawy 2011). Similarly, Uganda’s experience with the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) revealed the limits of a military-first strategy, as peace talks and amnesty ultimately weakened the group (Smock 2008).

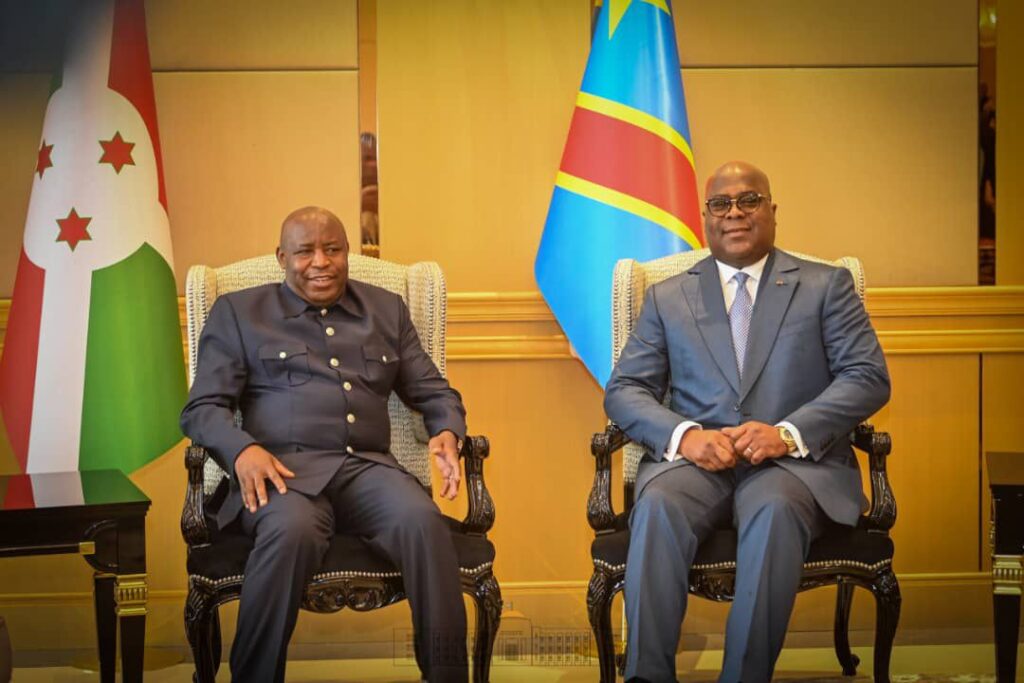

In DRC, Tshisekedi’s hardline stance risks not only prolonging the conflict with AFC/M23 but also destabilizing the already fragile regional alliances. Countries such as Rwanda,Burundi and Uganda are implicated in the DRC’s internal affairs, with each having vested interests in the eastern DRC’s outcome due to economic, security, and political concerns.

Complex Geopolitics: The Regional Influence

The geopolitical context of the Great Lakes region heavily influences the DRC’s approach to handling AFC/M23 rebel coalition group. Neighboring countries, particularly Rwanda and Uganda, have frequently been accused of supporting rebel groups within the DRC. President Felix Tshisekedi has specifically accused Rwanda of backing AFC/M23 militarily. UN experts reported that between 3,000 to 4,000 Rwandan soldiers were allegedly fighting alongside AFC/M23 rebels in eastern North Kivu. While Rwanda denied this, it later acknowledged having troops and missile systems in eastern DRC, citing security concerns and a Congolese troop buildup near its border (Lederer, 2024).

Tshisekedi’s refusal to engage in direct dialogue is partly influenced by the perception that negotiating with AFC/M23 could empower foreign-backed insurgents, potentially undermining Congolese sovereignty. However, this hardline approach fails to account for the complex regional alliances and cross-border dynamics that sustain the AFC/M23 rebel movement.

The previous deployment of peacekeeping forces by the East African Community(EAC) and the current deployment of the Southern African Development Community (SADEC) in eastern DR Congo provides a regional approach to conflict stabilization. However, without a pathway to reconciliation or peace talks with the AFC/M23 rebel group, these efforts may have limited impact. The DRC’s history shows that rebel groups often adapt to military pressure, regrouping or splintering when no peaceful alternative exists. Tshisekedi’s uncompromising stance risks strengthening AFC/M23 and similar groups, as it signals that peace is only possible through surrender.

Is a No-direct Negotiation with AFC/M23 Approach Sustainable?

The sustainability of Tshisekedi’s approach depends on whether the military can decisively defeat AFC/M23; a goal that remains challenging as the DRC’s armed forces are overstretched. Despite the Luanda Peace Process, the government’s refusal to negotiate with AFC/M23 creates a zero-sum situation focused solely on military victory, leaving little room for the broader needs of peacebuilding, community reintegration, and long-term stability.

Additionally, Tshisekedi’s uncompromising stance may risk eroding public support, particularly among the Kivu region’s residents who have long suffered insecurity and displacement with limited state protection despite the state of emergency declared on 6 may 2021 by the government in order to fight armed groups. . As civilians continue to face the impacts of ongoing violence, this approach could appear more concerned with political and military objectives than with human security. A military-focused strategy may achieve short-term goals but risks alienating communities critical to lasting peace.

Alternatives: Pathways to Sustainable Peace

Critics suggest that Tshisekedi’s government should consider alternative approaches to address the AFC/M23 insurgency, such as engaging in indirect or mediated negotiations through trusted intermediaries. Many interpret Tshisekedi’s visit to Kampala on November 30, 2024, as an indication of potential indirect talks with AFC/M23 rebel coalition group, with President Yoweri Museveni possibly acting as a mediator.

Though Tshisekedi’s government may publicly refuse direct talks with the AFC/M23 rebel coalition group, a secret strategy could be beneficial. A similar approach was used in South Africa, where behind-the-scenes negotiations between the African National Congress (ANC) and the apartheid government ultimately led to the end of apartheid (De Klerk, 2002). Such covert discussions need not imply compromising with insurgencies; instead, they could open pathways for de-escalation and frameworks for reintegration or political participation for groups willing to disarm.

Additionally, Tshisekedi’s administration could strengthen local governance structures and address socioeconomic grievances in the kivu provinces; By investing in development projects and enhancing local infrastructure, the government can build trust with local populations, reducing the appeal of rebel groups that often exploit these communities’ frustrations and vulnerabilities. Community-led peace initiatives and dialogues have been effective in other post-conflict settings, like Liberia and Sierra Leone, where local buy-in proved crucial for sustainable peace.

Conclusion

The question of whether peace can be achieved without dialogue is central to understanding Tshisekedi’s hardline stance on AFC/M23 rebel coalition group. While military action is vital for defending national sovereignty, an outright refusal to engage risks perpetuating violence and instability. In the complex landscape of eastern DRC, a strategy that blends military pressure with diplomatic outreach could provide a more sustainable path forward.

As Desmond Tutu once said, “if you want peace, you don’t talk to your friends; you talk to your enemies.” Tshisekedi’s administration now faces a critical choice: continue with a military-first approach or embrace a pragmatic, multi-faceted strategy. Lasting peace in the Kivu region will likely require more than battlefield victories; it will depend on dialogue, diplomacy, and the rebuilding of trust with communities affected by years of conflict.

Works Cited

ReliefWeb. (2023, Mars 23). Relief Web. Retrieved from Actor Profile: The March 23 Movement : Reliefweb.int

Africanews. (2023, December 15). Africa News. Retrieved from Democratic Republic of Congo: africanews.com

Ottaway, M., & Hamzawy, A. (2011, January 4). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from The comprehensive Peace agreement: carnegieendowmwment.org

Smock, D. (2008, February). United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved from Lord’s Resistance Army Peace Negotiations:an update from Juba: usip.org

De Klerk, E. (2002, December). South Africa’s negotiated transition:context,analysis and evaluation. Retrieved from Conciliator Resources: c-r.org

Lederer, E. M. (2024). UN experts:Between 3,000 and 4,000 Rwandan troops are in Congo operating with the M23 rebel group. AP.

Pingback: Afrika Dossier Sonderausgabe: – Canossa-Republik